When Yuri!! on Ice was announced, fans took notice. Director Sayo Yamamoto has amassed something of a cult following among feminist anime fans in the US for her full-length series Michiko and Hatchin and The Woman Called Fujiko Mine, which explicitly challenged the roles of women in popular fiction. She’d also directed the beautiful figure skating short “Endless Night” for Animator Expo, so it wasn’t exactly a shock when it was announced she’d direct a TV series with a similar concept. The big question was, when she’s primarily told stories about women and for women, what would a series featuring men be like coming from her?

The answer, it turns out, is something just as beautiful and subversive as her previous works. Much digital ink has been spilled about the beauty of the relationship between Yuri and Victor and about how revolutionary it is for both Yuris to make feminine expression integral parts of their routines. This is absolutely true, and I don’t have much to add to that conversation. I was, however, struck by how the secondary cast came across as well-rounded humans with lives of their own, even with limited screen time. In shows focused around male characters, the female cast tends to suffer, reduced to satellite characters with little purpose in life except their relationship to the male protagonists. Yamamoto and co-creator Mitsurou Kubo, however, fill Yuri’s universe with intelligent, capable women instrumental in shaping his life and his story, and the show is much stronger for it.

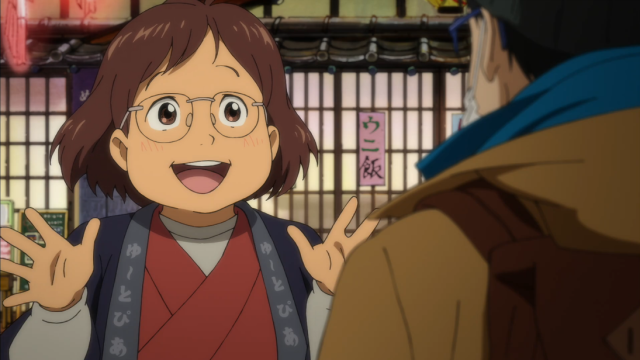

Like many sports anime, Yuri on Ice can be divided roughly into two parts: the training arc and the tournament arc. The training takes place largely in Hasetsu, Yuri’s hometown, and most of the characters are friends and family who have known him for his entire life. The three most powerful influences are his childhood crush Yuko, his dance teacher Minako, and his mother Hiroko. All three are intelligent, hard-working women, and two of them are small businesswomen. Minako is an accomplished dancer, runs a dance studio, and also operates a small snack club. Yuko is a working mother of three feisty six-year-olds. Hiroko helps run Yu-topia, Hasetsu’s only remaining hot spring resort.

Yuko Nishigoori is introduced as Yuri’s childhood friend and former crush, two years his senior. In flashbacks, we see how she defended him against the boy who bullied him for his weight and how she practiced Victor’s routines with him. As an adult, she has married that same bully, who has presumably matured, and works at the ice rink where they once practiced together. Her warm, comforting personality gave solace to the perpetually anxious Yuri when they were children. Yuri is sensitive about being pitied, as shown in the anecdote he tells Victor about pushing away a girl who tried to hug him when a mutual friend of theirs was injured, but his enduring friendship with Yuko shows that she supported him without ever crossing that line. Her warmth plays an important role in the first arc as well; she is the only one in Hasetsu able to befriend the prickly teenager Yuri Plisetsky. While everyone is celebrating Yuri’s victory in their Hot Springs on Ice competition, she’s the only one who notices him leaving and runs out to say goodbye to him. Her friendship also shows that she has managed to develop fluency in English, which is quite rare in small-town Japan. The two maintain something of a friendly relationship, e-mailing even after Yurio returns to Russia, and she appears in Yurio’s mind’s eye when he reflects on agape, the Greek concept of unconditional platonic love, which his short program is based on. She is also raising six-year-old triplets named Axel, Loop, and Lutz (who’s names are probably the most regrettable decision she’s made), which would make her only nineteen years old when she had them. The three girls are precocious and feisty, and Yuko often has to battle them to get them to go to bed on time and stop abusing social media. Her interactions with her daughters also show that she isn’t just saccharine sweet, since they often involve her scolding them for staying up too late.

Minako Okukawa, Yuri’s dance teacher, has a less maternal personality but may have been an even stronger influence in nurturing his talent. Before settling down in Hasetsu, Minako traveled the world as a dancer and even won the Prix Benois de la Danse, one of the most prestigious awards in ballet. It’s never explained why she came to Hasetsu as a dance teacher – she could easily make a comfortable living in a city where dance is more in demand. As it is, her studio is struggling to enroll students, especially as the population of Hasetsu declines. In order to make ends meet, she also runs Kachu snack bar. The meaning of “snack bar” in Japan is somewhat different from what Anglophones may expect; rather than what you’d see at say, an arcade serving nachos and popcorn, Japanese snack bars are something like low-rent hostess clubs. The booze is overpriced and many customers purchase whole bottles that they can return to; the owner is usually an older woman; and it’s part of the staff’s job description to flirt and drink with the male customers and listen to their woes. The emotional labor she must perform, on top of operating two businesses, just go to show how incredibly hard-working she is. Although Minako lacks Yuko’s sweetness, she was important to Yuri. Her dance studio was a haven to him during his frequent bouts of anxiety, and she was the one who recommended he try figure skating. When Yuri returns to Hasetsu from Detroit, she continues to play a major role in his life, picking him up from the train station to take him home and later teaches him how to “move like a woman” when he knocks on her door in the middle of the night. She accompanies Yuri as he moves up in the Grand Prix, although that wasn’t purely altruism; she just really wanted to see the handsome male skaters up close.

The latter half of the series follows Yuri through the Grand Prix. Although Yuri’s competitors are male, two in particular have their performances defined by their relationships with women. Georgi Popovich, a Russian skater, was recently dumped by his girlfriend, an ice dancer named Anya, for another man. For his short program, he assumes the role of the wicked fairy in Sleeping Beauty, imagining himself cursing her as she begs for mercy. He scores well, but those who know the story behind his performance become uncomfortable. “I can almost hear her terrified voice,” comments Mila, a female skater who trains under the same coach. In his free skate, however, he imagines himself as a prince coming to her rescue, tearfully begging her forgiveness and promising to save her as he pictures himself kissing her while she sleeps clutching a smartphone displaying pictures of her with her new paramour. Anya, who is in no need of saving, has no patience for Georgi’s delusions. She realizes what’s going on during his free skate and catches his eye as she stands up to leave. When he smiles at her hopefully, she scowls and gives him a thumbs down, causing him to scream in despair in the middle of his performance. There’s not really any way to know what happened between her and Georgi but, judging on how he imagines himself at once as witch and savior, cursing her for leaving him while simultaneously telling himself she needs to be rescued from her new lover, it’s easy to fill in the blanks and see that he was probably a clingy, jealous boyfriend. It’s a common “nice guy” mentality – they tell themselves that they are the best possible man for a woman, that she’s a victim of assholes, all while condemning them as vapid whores for sleeping with other men. There is no mistaking the message meant to come across: this behavior is creepy and unacceptable, and Anya is better off without him. We don’t see much of Anya outside of the lens of her relationship with Georgi, but her role in his story still tells a powerful message.

The second pair is Michele and Sara Crispino, a pair of twins from Italy with a codependent relationship nearly bordering on incest. Michele is obsessively protective of his sister – the first time we see them, Michele is shouting at another skater for expressing interest in her in the elevator. For his short program, he dresses as a knight and, much like how Georgi pictured Anya, thinks of how he must protect his little sister as he skates. “I’ve defeated every single man who’s tried to approach Sara so far,” he thinks. “I want to skate with my sister forever!” Although he claims his love isn’t physical, he’s still as possessive as if they were a couple and not siblings. Sara, on the other hand, recognizes how unhealthy their relationship is, thinking “If something doesn’t change, both of us will go down.” They are, after all, twenty-two years old; it’s not healthy for him to be the only man in her life and vice versa, or to be the sole motivators for each other. The next day she confronts him, telling him, “I will go to the Grand Prix final with or without you. So you need to win without my support, too, Mickey.” He clings to her, whining about how he could only come this far because of her, and she shouts at him, “I can skate without your love, and I’ll start dating!” Her message is clear – she is stronger than he thinks she is, and he needs to learn to be strong too. It’s not healthy to be solely motivated by your relationship to another person, and Sara is sick of being held up on that pedestal by Michele. She doesn’t want to be his muse or his committed partner; she only wants independence. She watches his free skate from the stand rather than rinkside, and weeps at his beautiful performance as he mentally bids goodbye to her. After his program, she hugs him and apologizes for talking to him so harshly, but reaffirms that she made the right choice. “We’re better apart, after all!” Michele and Sara’s relationship is fundamentally different from Georgi and Anya’s, but there are strong parallels in the rejection of dependence and the need for independence. Female independence is a major recurring theme in Sayo Yamamoto’s works, and it’s wonderful she managed to work it into a story fundamentally about men.

Yuri on Ice has two basic types of female characters: the hard-working, independent women who fundamentally shaped Yuri as a person, and accomplished artists who are unwilling to accept clingy, unhealthy relationships with men. It’s wonderful to see a cast of women who live life on their own terms and play fundamental roles in the male protagonist’s life while very much being their own people. Yuri on Ice won’t go down in history as a feminist masterpiece, but its unusual, even revolutionary attitude toward gender relations deserves to be recognized and should be remembered for a long time.

Good post. Gave me a deeper appreciation for this anime. 😀

LikeLike

This was an excellent post. It is one of things I loved about this anime is that the characters mostly feel like real people and while I talked about the male cast members the same care has been given to the female characters regardless of how little screen time some of them have been given. The snapshots of their lives feel like authentic moments that we are catching glimpses of even while we keep getting drawn back to the competition.

Thanks for sharing this.

LikeLike

A great article. I usually feel a bit let down by female characters in sports anime, but Yuri on Ice utilized every bit of screentime to fit in as many women as possible.

Another female character I loved was Yurio’s choreographer, Liliya Baranovskaya. She is also an accomplished, retired prima ballerina like Minako, and also divorced. But what I loved about her the most was how her strict lessons to Yurio paid off in the end! Often than not strict female characters are seen negatively, but in this case she really helped Yurio mature into his artistic vision.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree! I love Haikyuu but the manager fails the sexy lamp test pretty hard. Liliya is great and I love her, but unfortunately this post would have gotten way too long if I included all the female characters. Thus, I decided to focus on Anya and Sara

LikeLike

Pingback: In Case You Missed It | 100WordAnime

Great post. I agree, I really found myself enjoying the female characters, they were really well done.

LikeLike

Pingback: FEATURE: Found in Translation - Why I Love "Yuri!!! on ICE" | Yaoi Obsession

I was also pleasantly caught off guard by the women in YoI. Okay, I was pleasantly caught off guard by YoI in general but the treatment of female characters is part of that. My admittedly limited experience with male-centric sports anime is of women being one-dimensional or minor characters at best.

This was a great read and I enjoyed how you look deep into the characters listed and the way they’re presented.

LikeLike

Pingback: Feminist anime recommendations of 2016 - Anime Feminist

I went to that anime expecting the revolutionary good treatment of men’s love: and i came out with so much more.

Excellent article. Shows a perfect example that it doesn’t need to be about women in order to have them represented as actual people with lives, with the power to influence those around them: rather than only serve as lifeless characters with the sole purpose of develop the male characters.

LikeLike

Pingback: Must-read Monthly Monday (inaugural ed.) – The Animanga Spellbook